DOWN AND OUT IN MOSCOW

A VIEW FROM RUSSIA

Paul Lewis

Originally published Saga

Magazine, September 1993, pp. 18-22.

Nikolay

Andreevitch Yasinsky’s apartment is set back from Parkovaya

Street 15th, so called because it is the fifteenth of sixteen parallel

streets all called Ulitsa Parkovaya or Park Street which hatch the space

between Moscow’s outer ring motorway and a long wide road called Okrusnoy

Avenue. To the north lie the remains of the natural woodland on which this

estate was built and the blocks of flats on Parkovaya Street 15th seem

to have been placed among the fully grown trees without disturbing any that

were more than six feet from their walls.

War veteran Nikolay Andreevitch. He lost his leg during the battle

to relieve the siege of Leningrad, but today he cannot afford to buy the vegetables

he needs.

Trees

are the redeeming feature of Moscow’s dilapidated blocks of dreary flats which

officially house nine million and actually accommodate thirteen million. They

need redemption. At each address there are several buildings, set back from the

road. Nikolay’s is a good 200 yards from the pavement along unmade roads

relieved by scrap cars, earth playgrounds, and large rubbish containers. Four

doors lead into his building. Through the first and up six short flights of

stairs is apartment 85, building 5, number 42, Parkovaya Street 15 — home to

Ukrainian Nikolay, aged 72.

He

lost his left leg fighting to relieve the siege of Leningrad. “Where Pushkin

was wounded, Black River” — he is proud to have been wounded at such an

illustrious place. There is no lift in the building and the red and yellow

tiles on the concrete landings and stairs are broken and uneven. On every other

half-landing there is a rubbish chute. His front door is well locked and leads

to a small hallway which gives on to a tiny kitchen, through which there is a

balcony with a few plants. A second door leads to the bedsitting room where his

small box bed is part of his daytime furniture. A table covered with an old

carpet and a cheap settee fill the rest of the room. The finest objects are

large, framed photographs of him and his wife taken before the war.

He

has three rooms, though all are less than 12 feet square. One was his and his

wife’s, one was their daughter and son-in-law’s, the other was for his

grandson, his wife and their two-year-old daughter. Seven people crowded into

three rooms, a typically crowded Moscow family flat. But last year his wife

died of cancer and his daughter died of diabetes. A few months later his

grandson, a soldier, was killed in a shooting accident and his widow and their

baby have moved back to live with her parents. Now Nikolay Andreevitch lives

alone with his son-in-law Viktor Mikhailovitch. The three-roomed apartment is

too big for just the two of them. He weeps at the memory of the loved ones he

has lost.

Nikolay’s

pension is enough, he says. He gets 24,000 roubles a month — his flat costs him

just 85 roubles a month. Over the last year all flats in Moscow have been privatised

by the simplest possible means — handed over to the tenants. The 85 roubles

covers heating, water, and rubbish collection. In addition, he pays 20 roubles

for electricity and 106 roubles for the phone. Local calls are free. With the

basics taken care of, Nikolay still has almost all the 24,000 roubles a month

left for living.

It

is impossible to say simply what a rouble is worth. If you go into a bank with

pounds sterling you can buy 24,000 roubles for about £14 so his pension is

little more than £4 a week. But all state services, such as the flat and

electricity, are very cheap. A ride on the Metro, Moscow’s efficient

underground railway costs six roubles, about a third of a penny, for any

distance. A ride on a trolleybus or tram is four roubles. Conversely fruit, for

example, is very expensive. Two pounds of apples will cost 2,000 roubles, a

twelfth of a month’s pension. Even a pint of milk is expensive at 80 roubles, a

2lb bag of sugar costs 355 roubles. But Nikolay Andreevitch doesn’t think in

such quantities. “Five small carrots are 100 roubles. I need vegetables but I

cannot have them. I need the vitamins and I cannot buy them in the chemist.”

Nikolay’s

pension is enough for his needs because his diet is very poor. He never eats

fruit, he doesn’t like meat. It is just as well. Ham is 3,784 roubles a kilo at

a local shop. At about 25p a pound it sounds cheap, but not if you are living

on £14 a month. Nikolay Andreevitch lives on vegetable soup, porridge, which

Russians eat as a main course, potatoes and, at 24 roubles each, eggs. He never

goes out, except to return to his factory for some company during the day.

He

says, “I fought in the war. I was honoured at work. I was a technician in a

textile research plant and factory. But now life beats me greatly. I don’t know

why God does it. Under Stalin, after the war, he told us the price of bread. And prices came down each year. Now

inflation has robbed us. My wife and I had 5,000 roubles each in the bank. It

was good savings. Now it is worth nothing.”

The

rate of inflation in Russia is hard to grasp. Although it is now falling, it

was 2,600 per cent in 1992. Something which cost 100 roubles in January cost

2,700 roubles in December. To try to cope with the effects, the Government

raises the pension every three months. Pensions are now ten times what they

were nine months ago and sixty times what they were two years ago. If we had

inflation at the same level in Britain, the basic retirement pension would have

risen from £52 in 1991 to £3,120 a week in 1993. Despite the frequent increases

in pension, inflation soon destroys its value —by one third at the end of the

month in which the pension is paid; after three months when the next pension

rise is due it is worth less than half its original value.

Nikolay

had a reasonable job and his war injury ensures that his pension is higher than

the pay of many people still in employment. Other Russian pensioners are not so

fortunate, you can see them in their hundreds round every Metro station, in the

subways beneath Moscow’s broad avenues, and lining the busier streets. The city’s

poor have joined the market economy with a vengeance to try to scrape a living

with a few extra roubles. Some sell small bunches of cut flowers; others offer second-hand

clothes, a few sell kittens. But mainly they sell food.

They

even sell food outside Moscow’s central market in Svetnoy Boulevard. Inside the

market, pyramids of glossy fruit and plump vegetables are a testimony to the

fertile diversity of Russian soil and climate. The market has always been here,

even under the communist regime, and its Georgian stallholders have a

reputation for hard bargaining and high prices. On the street outside, it is

different.

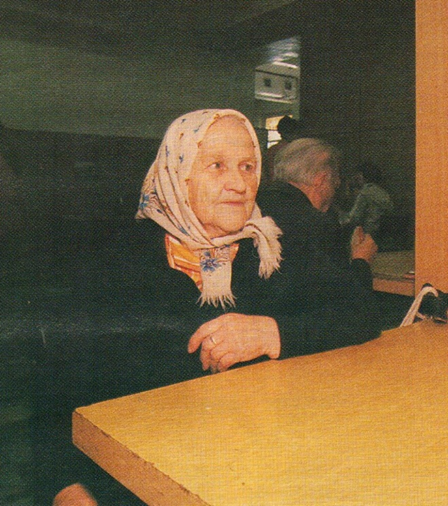

Lubov Vassilievna takes all day to

sell a couple of loaves and some milk —

she makes 17p.

Widow

Lubov Vassilievna, 79, wears a colourful scarf and an orange-coloured cardigan

over a print dress. Her wares are displayed on a cardboard box: one loaf and a

one litre carton of milk. In her bag there are two more of each. It takes her

all day to sell them and she makes less than 300 roubles (17p). She worked for

20 years in a shoe factory after bringing up her children. Her pension is 8,000

roubles (£4.45) a month. She told me, “I cannot remember when I last ate meat

or sausages. I eat milk, potatoes, and bread but no butter, just oil to fry

them in. I have no fruit or vegetables but I may be able to afford them later

in the year when they get cheaper.”

Russian

pensions are related to earnings. A wife who has a pension of her own gets no

widow’s pension when her husband dies. Lubov Vassilievna is suffering from

widowhood after a short, low-paid, working life when her children had grown up.

Perhaps the children helped her now? She smiled: “I have a daughter, a

granddaughter and two great grandchildren. I help them from my pension and what

I make here. They need help because of the expense of everything and the new

problem of unemployment. Soon I will be 80 and I am looking forward to that

because my pension will be a bit more then. My main worry is that I have high

blood pressure and medicines are very hard to get. It is a worry to know that

you cannot get them when you need them.”

Like

most of the women lining this busy thoroughfare, Lubov sells food on the street

which she has bought in ordinary shops. Her customers are workers who are too

busy or too lazy to queue for it themselves. Although there are no longer the

chronic shortages and long queues which characterised daily life under

communism, buying food is still a lengthy process. Choice is very limited in

the small, local grocery shops which are all called, simply, Produkti

(products).

One

of these is nearby in a dirty, drab building. The windows are empty. Inside

there are three counters: one stocks milk and cereals, another meat, mainly

dried or preserved in some way, and a third vegetables. There are just six or

seven different items at each counter with half a dozen people queuing for

them. Patches of bare concrete show through the broken floor tiles; some new

plastering is left unpainted. If the lighting had not been so poor, it would

look even worse. Prices displayed on torn pieces of rough card show that butter

is 1,180 roubles a kg (30p a pound), tea is 231 roubles for 100g (14p a

quarter), and sugar is 355 roubles a kilo (9p a pound). The prices seem low

when converted into sterling but they are not when they have to be found out of

a pension consisting of just a few pounds a month.

At

each counter there is a small queue. Occasionally, a veteran or disabled person

goes to the head of the queue, which by convention they may, and they will be

served at once. Others wait patiently. Once the few items have been chosen and

the price calculated, either mentally or, in difficult cases, on an abacus, the

customer is given a ticket. This process is repeated at each counter and the

tickets must be taken to yet another queue at the central cash desk. In turn,

the totals on the tickets are added — on another abacus — before the total is

finally entered on a new Casio till! The customer takes the receipt to each

counter in turn to collect the groceries. By enduring this long process then

re-selling the goods on the street for a small profit, Lubov, like thousands of

other women across Moscow, sells her time and patience to supplement her pension.

Fifty

yards in front of the Izmaylovo International Hotel is the Ismaylovskaya Metro

station. Forty women stand in two lines like an honour guard for the passengers

emerging from its entrance. Maria, 63, holds aloft a large salami and a small

plastic bag full of tomatoes. Occasionally a passer-by shows interest and asks

the price. “My pension is 10,000 roubles (£5.55) a month because I had a

low-paid job in a meat factory where I worked for 15 years. My husband died two

years ago. I am here maybe two or three times a week, I make perhaps 1,000 or

1,500 roubles (55p-83p),” she said. Next to her is Alexandra, 70, selling milk.

“My father was imprisoned by Stalin. He was taken when I was 14, so I had no

education and could not get a good job, so I have a small pension. I buy milk

in the shop for those who have not got the time to queue. I think this is a

good use of my time and I make a few roubles.”

Not

everyone buys the produce they sell. Outside a cheese shop in the south suburbs

of Moscow, Ivan Mikhailovitch sits in front of a box on which are three

portions of rocket, a kind of wild lettuce, replenished by the sackful. “My

pension is 10,000 roubles (£5.55). I collect this in the woods and then sell it

here two or three times a week. It is 50 roubles (3p) a portion.”

Ivan Mikhailovitch supplements his

pension by selling wild lettuce. He makes

around 3p a portion.

If

the central market is the best in Moscow then Tishinksky market is the worst.

On a piece of waste ground, in front of derelict buildings, using sheets of

newspaper for stalls, Moscow’s poor sell to each other: rusty blunt drill bits

and a handful of used brake shoes. Sergei, is selling his grandchildren’s old

shoes, three out-of-date reel-to-reel tapes for which he claims to have a

buyer, and four small steel hinges. At the entrance a woman sits in front of a

small tray on which are various boxes of medication, dirty and old, but items

which are hard to find in Moscow’s chemist shops.

Inside

the market is Praskovia Ivanovna who lives alone in a one-room flat and sells

empty 1.5 litre plastic bottles for 15 roubles each (less than 1p). Aged 80,

her pension is 15,000 roubles (£8.33) a month. It is enough to live on, she

says, but adds: “I haven’t eaten a tomato all year because they are too

expensive. I sell my things here for almost nothing.”

A

recent survey by the charity Care International found that pensioners living

alone were the most vulnerable here. In the south west corner of Moscow, near

the university, the International Protestant Church organises a modest response

to this problem, providing meals for Moscow’s poorest and loneliest pensioners

in what it calls a soup kitchen – a stolovaya or canteen. These stolovayas

provide more than 10,000 meals a day to needy, people, mainly pensioners. The

stolovaya I visited feeds 300 each lunchtime, staffed by volunteers and

students, many from Nigeria who are in Moscow studying engineering. On offer

today is a thin vegetable soup, plain pasta served with thick brown porridge, a

hard boiled egg, two pieces of dark bread, and a glass of tea.

Anna

Nikolayevna Volodina, 81, wears a white patterned scarf tightly drawn over her

round face. Her black dress is old and worn and covered by a blue cardigan. Her

shoes are thin. The Russian language has a wonderful term of love and respect

for its older women — babushka or grandmother. If anyone personifies it, Anna

does. She looks at her soup, pasta, and porridge and peels her egg. “The food

here is very delicious,” she says. “I worked all my life in the Dulova china

factory where I painted designs on cups and plates. After I retired I got 52

roubles pension and that was plenty. Now I get 8,000 roubles (£4.44) a month

and it is not enough. I respect those who work in factories, but I do not

respect these businessmen and speculators. They are really workers but they don’t

want to work.”

Anna Nikolayevna Volodina

personifies the Russian Babushka (grandmother). The stolovaya’s (soup kitchen) food is “very delicious”, she says.

Her

family, two sons and numerous grandchildren and great-grandchildren still live

in Dulova, about 60 miles from Moscow. She remarried a Muscovite late in life

and is now a widow but now that she is registered as a Moscow resident it is

hard for her to move away.

“My

sons don’t help me because they have many children themselves. One is a

mechanic but wages are low and unemployment is now a constant fear. I live in a

communal flat, I have one room and there are two other rooms with young men in

them. We share a bathroom and kitchen. They don’t help me. No, if I’m not

careful they would steal from me. I have bread and butter and tea for breakfast

but I do not have enough to eat — the food here is very good. Hot meals of the

sort I like. Really I am young, my life is young, I am hoping to live a very

long time. I am always smiling and that is the important thing.” Her deeply

lined white face breaks into a smile as the beauty and mischief break through

the patient endurance of this wonderful babushka.

When

flats were allocated by the state, the housing shortage was dealt with by

putting childless people in communal flats. Unrelated, and often incompatible

single people or couples, like Anna and her flatmates, would share three rooms,

with common facilities, waiting for the time when they could get some privacy.

It could take years but technically they were “housed”.

Viktor is homeless. He lost his

documents so he receives no pension. “I sleep

where I am”.

Now

that the state no longer controls housing, there is real homelessness. Viktor

is 57 and an epileptic. Married twice and an officially registered resident of

Moscow, he is homeless. His dark face framed by a flowing brown beard, his

dark-coloured, thick clothes and shoes tied with string. He smells of strong

Russian tobacco. He eats at the stolovaya. “I was a carpenter. I have been

married twice but now I sleep where I am. All my documents were stolen so I get

no pension. Sometimes I collect old bottles and return them for a few roubles.

Or I just beg. I get perhaps 100 or 200 roubles (5p-11p) a day. I eat here free

but at other canteens I must pay 72 roubles (4p) for a plate of soup.”

John

Melin is a Lutheran minister from Minneapolis, currently resident with the

International Protestant Church in Moscow which runs the stolovaya. As people

come and go they thank and praise him for his kindness. One woman stops to say,

“I have worked for 63 years yet I have to come here for my food. God bless the

church and God bless the Americans who help us.”

John

explains, “We wanted to share with the people who were needy during the

difficult transition from communism. This soup kitchen is our response to that

need. We provide healthy traditional meals for 15 to 18 cents (10p-12p) each.

Every dollar we are given goes straight to those in need. It is a food sharing

ministry and I want to stress we provide service not just food, an opportunity

to talk with people. Here they can sit, and be served, and talk. We do not proselytise.

Our witness is in our service.”

A

soup kitchen can never be more than a stop-gap measure to deal with the

economic problems which

create the terrible poverty prevalent in Moscow. Under the communist system,

the welfare of older people was shared be-tween relatives and an elaborate

system of organised care. Charities and voluntary organisations were banned by

a state which had to seem to provide everything its people needed. But when the

communist regime collapsed following the rapid political changes which followed

the attempted coup in August 1991, the structures it supported went with it.

The gap is slowly being filled by charitable efforts, according to Megan Bick,

director of the Moscow office of the BEARR Trust (British Emergency Action in Russia

and the Republics), an English charity devoted to helping the countries of the

former Soviet Union.

Megan

said, “The Trust keeps in touch with the local needs and channels help, from

people in Britain, such as money or goods or technical aid about how the

voluntary sector works.”

Prospekt

Mira, or Peace Avenue, is a broad boulevard running due north out of Moscow

past the exhibition of economic achievements which lies beneath a soaring

titanium statue of a space rocket pointing skywards. Close to these monuments

to Russia’s past a small group of people is trying to create the human side of

its future.

The

Alexeyevskiy district consists of 300 blocks of flats and is home to 80,000

people. It was built for those who worked on the Metro and among them are now

an estimated 35,000 pensioners. Here, in a damp basement office that used to

house communist party meetings, the Alexeyevskiy Fund, with some assistance

from the BEARR Trust, is developing services for them. Its director is Tatiana

Yurievna Pavlicheva, who used to work as a metallurgist in the defence industry

until, in 1990, she became involved in distributing humanitarian aid. “It was a

big problem about how to give aid to people who needed it and stop well off

people from grabbing it. Doing this work made me realise what problems existed

and I started trying to see what I could do. God wouldn’t forgive me if I didn’t

do something.”

Her

first step is to carry out a survey of the pensioners in the area and she

expects to find about 1,000 who need help to cope alone. Like any western

charity, the Alexeyevskiy Fund has to raise its own money. Tatiana appears to

have found a uniquely Russian way of doing that, using the value of the newly

privatised flats which these older people now occupy.

She

explained: “An old woman lives alone and needs help. And there is a businessman

who would like to have the flat when she dies. So the Fund sits in the middle.

We contact the businessman, telling him that there is a flat of such a size in

such a district and it is owned by a woman born in such a year but no other

details. If he agrees, we get a lawyer to draw up documents so he pays money to

our Fund and he will receive the flat in the end when she dies. The Fund then

provides her with the services she needs for the rest of her life.”

Tatiana

admits that with high inflation and investors wanting a quick return on their

money, it is hard to persuade Russia’s new entrepreneurs to support the Fund

now, in exchange for a possible return in several years’ time. But already one

local businessman is paying some salaries in exchange for the promise of a flat

when its octogenarian owners die. With salaries of 15,000 roubles (£8.50) a

month and some flats worth $50,000 (£33,500) it could end up a very good deal. Already

documents are being drawn up to allow the Fund to share in the profit to pay

for some of its future projects.

It

is a practical answer to the terrible problems which their older people face.

They live in the biggest country on the planet, packed with natural resources.

They have some of the best science and technology in the world and an enviable

heritage of literature and art. They could have so much. But many have so

little.

Translation:

Lyudmila Alekseevna Cromova

Pictures:

Grigory Dukor and Paul Lewis

Vs. 1.00

20 April 2022